The author is drawing a bit of a long bow when attributing the devastation and desertification from inappropriate broadscale industrial cultivation to primitive woman and her digging stick, but it still looks like some interesting holiday reading...

Tree Crops: A permanent agriculture, by J. Russell Smith, published in 1929.

"This book is written to persons of imagination who love trees and love their country, and to those who are interested in the problem of saving natural resources—the basis for civilization."

PART 1 The Philosophy

1. The Problem

"I stood on the Great Wall of China near the borders of Mongolia. Below me in the valley, standing up square and high, was a wall that had once surrounded a city. Of the city only a few mud houses remained, scarcely enough to lead one's mind back to the time when people and household industry teemed within the protecting wall. The slope below the Great Wall was cut with gullies, some of which were fifty feet deep. As far as the eye could see were gullies, gullies, gullies—a gashed and gutted countryside.

The little stream that once ran past the city was now a wide waste of coarse sand and gravel which the hillside gullies were bringing down faster than the little stream had been able to carry them away. Hence, the whole valley, once good farm land, had become a desert of sand and gravel, alternately wet and dry, always fruitless. It was even more worthless than the hills.

Beside me was a tree, one lone tree. That tree was locally famous because it was the only tree anywhere in that vicinity; yet its presence proved that once there had been a forest over most of that land—now treeless and waste.

The farmers of a past generation had cleared the forest. They had plowed the sloping land and dotted it with hamlets. Many workers had been busy with flocks and teams, going to and fro among the stocks of grain. Each village was marked by columns of smoke rising from the fires that cooked the simple fare of these sons of Genghis Khan. Year by year the rain has washed away the loosened soil.

Now the plow comes not, only the shepherd is here with his sheep and goats—nibblers of last vestiges. The hamlets are shriveled or gone: Only gullies remain—a wide and sickening expanse of gullies, more sickening to look upon than the ruins of fire. Forest—field—plow—desert—that is the cycle of the hills under most plow agricultures—a cycle not limited to China.

China has a deadly expanse of it, but so have Syria, Greece, Italy, Guatemala, and the United States. Indeed Americans are destroying soil by field wash faster than any people that ever lived—ancient or modern, savage, civilized, or barbarian.

We have the machines to help us to destroy as well as to create. We also have other factors of destruction, new to the white race and very potent. We have tilled crops—corn, cotton, and tobacco.

Europe did not have these crops. The European grains, wheat, barley, rye, and oats, cover all of the ground and hold the soil with their roots. When a man plows corn, cotton, or tobacco, he is loosening the earth and destroying such hold as the plant roots may have won in it. Plowing corn is the most efficient known way for destroying the farm that is not made of level land.

2. The Idea

Again I stood on a crest and scanned a hilly landscape. This time I was in Corsica. Across the valley I saw a mountainside clothed in chestnut trees. The trees reached up the mountain to the place where coolness stopped their growth; they extended down the mountain to the place where it was too dry for trees.

This chestnut orchard (or forest as one may call it) spread along the mountainside as far as the eye could see. The expanse of broad-topped, fruitful trees was interspersed with a string of villages of stone houses.

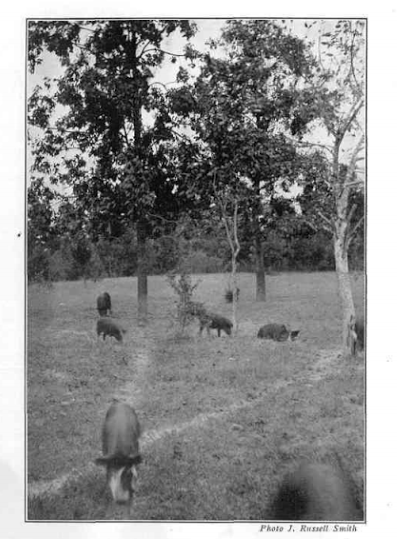

The villages were connected by a good road that wound horizontally in and out along the projections and coves of the mountainside. These grafted chestnut orchards produced an annual crop of food for men, horses, cows, pigs, sheep, and goats, and a by-crop of wood.

Thus for centuries trees had supported the families that lived in the Corsican villages. The mountainside was un-eroded, intact, and capable of continuing indefinitely its support for the generations of men.

Why are the hills of West China ruined, while the hills of Corsica are, by comparison, an enduring Eden? The answer is plain. Northern China knows only the soil-destroying agriculture of the plowed hillside. Corsica on the contrary has adapted agriculture to physical conditions; she practices the soil saving tree-crops type of agriculture..."

“Our present agriculture is based primarily on cereals that came to us from the unknown past and are a legacy from our ancient ancestress —primitive woman, the world's first agriculturist. Primitive woman gleaned the glades about the mouth of her cave for acorns, nuts, beans, berries, roots, and seeds. Then came the brilliant idea of saving seed and planting it that she might get a better and more dependable food supply. Primitive woman needed a crop in a hurry, and naturally enough she planted the seeds of annuals.

Therefore, we of today, tied to this ancient apron string, eat bread from the cereals, all of which are annuals and members of the grass family. As plants the cereals are weaklings. They must be coddled and weeded. For their reception the ground must be plowed and harrowed, and sometimes it must be cultivated after the crop is planted. This must be done for every harvest. When we produce these crops upon hilly land, the necessary breaking up of the soil prepares the land for ruin—first the plow, then rain, then erosion. Finally the desert.

Must we continue to depend primarily upon the type of agriculture handed to us by primitive woman? Many of the present day grains, grasses, and cereals would scarcely be recognized as belonging to the families that produced them. Present day methods of cultivation but dimly recall the sharpened stick in the hand of primitive woman. But we still depend chiefly on her crops."

Tree Crops: A permanent agriculture, by J. Russell Smith, published in 1929.

"This book is written to persons of imagination who love trees and love their country, and to those who are interested in the problem of saving natural resources—the basis for civilization."

PART 1 The Philosophy

1. The Problem

"I stood on the Great Wall of China near the borders of Mongolia. Below me in the valley, standing up square and high, was a wall that had once surrounded a city. Of the city only a few mud houses remained, scarcely enough to lead one's mind back to the time when people and household industry teemed within the protecting wall. The slope below the Great Wall was cut with gullies, some of which were fifty feet deep. As far as the eye could see were gullies, gullies, gullies—a gashed and gutted countryside.

The little stream that once ran past the city was now a wide waste of coarse sand and gravel which the hillside gullies were bringing down faster than the little stream had been able to carry them away. Hence, the whole valley, once good farm land, had become a desert of sand and gravel, alternately wet and dry, always fruitless. It was even more worthless than the hills.

Beside me was a tree, one lone tree. That tree was locally famous because it was the only tree anywhere in that vicinity; yet its presence proved that once there had been a forest over most of that land—now treeless and waste.

The farmers of a past generation had cleared the forest. They had plowed the sloping land and dotted it with hamlets. Many workers had been busy with flocks and teams, going to and fro among the stocks of grain. Each village was marked by columns of smoke rising from the fires that cooked the simple fare of these sons of Genghis Khan. Year by year the rain has washed away the loosened soil.

Now the plow comes not, only the shepherd is here with his sheep and goats—nibblers of last vestiges. The hamlets are shriveled or gone: Only gullies remain—a wide and sickening expanse of gullies, more sickening to look upon than the ruins of fire. Forest—field—plow—desert—that is the cycle of the hills under most plow agricultures—a cycle not limited to China.

China has a deadly expanse of it, but so have Syria, Greece, Italy, Guatemala, and the United States. Indeed Americans are destroying soil by field wash faster than any people that ever lived—ancient or modern, savage, civilized, or barbarian.

We have the machines to help us to destroy as well as to create. We also have other factors of destruction, new to the white race and very potent. We have tilled crops—corn, cotton, and tobacco.

Europe did not have these crops. The European grains, wheat, barley, rye, and oats, cover all of the ground and hold the soil with their roots. When a man plows corn, cotton, or tobacco, he is loosening the earth and destroying such hold as the plant roots may have won in it. Plowing corn is the most efficient known way for destroying the farm that is not made of level land.

2. The Idea

Again I stood on a crest and scanned a hilly landscape. This time I was in Corsica. Across the valley I saw a mountainside clothed in chestnut trees. The trees reached up the mountain to the place where coolness stopped their growth; they extended down the mountain to the place where it was too dry for trees.

This chestnut orchard (or forest as one may call it) spread along the mountainside as far as the eye could see. The expanse of broad-topped, fruitful trees was interspersed with a string of villages of stone houses.

The villages were connected by a good road that wound horizontally in and out along the projections and coves of the mountainside. These grafted chestnut orchards produced an annual crop of food for men, horses, cows, pigs, sheep, and goats, and a by-crop of wood.

Thus for centuries trees had supported the families that lived in the Corsican villages. The mountainside was un-eroded, intact, and capable of continuing indefinitely its support for the generations of men.

Why are the hills of West China ruined, while the hills of Corsica are, by comparison, an enduring Eden? The answer is plain. Northern China knows only the soil-destroying agriculture of the plowed hillside. Corsica on the contrary has adapted agriculture to physical conditions; she practices the soil saving tree-crops type of agriculture..."

“Our present agriculture is based primarily on cereals that came to us from the unknown past and are a legacy from our ancient ancestress —primitive woman, the world's first agriculturist. Primitive woman gleaned the glades about the mouth of her cave for acorns, nuts, beans, berries, roots, and seeds. Then came the brilliant idea of saving seed and planting it that she might get a better and more dependable food supply. Primitive woman needed a crop in a hurry, and naturally enough she planted the seeds of annuals.

Therefore, we of today, tied to this ancient apron string, eat bread from the cereals, all of which are annuals and members of the grass family. As plants the cereals are weaklings. They must be coddled and weeded. For their reception the ground must be plowed and harrowed, and sometimes it must be cultivated after the crop is planted. This must be done for every harvest. When we produce these crops upon hilly land, the necessary breaking up of the soil prepares the land for ruin—first the plow, then rain, then erosion. Finally the desert.

Must we continue to depend primarily upon the type of agriculture handed to us by primitive woman? Many of the present day grains, grasses, and cereals would scarcely be recognized as belonging to the families that produced them. Present day methods of cultivation but dimly recall the sharpened stick in the hand of primitive woman. But we still depend chiefly on her crops."